“Privileging the wealthy and disadvantaging the financially needy are ‘inextricably linked.’”

Student recipients of need-based financial aid brought a class action against 16 elite universities for allegedly conspiring to limit the amount of financial aid awarded to students in a way that violates a higher education exemption to antitrust laws.

Filing in federal court in Chicago on Jan. 9, 2022, the students argue that the schools do not qualify for an exception to antitrust laws that allows need-blind schools to collaborate on the formulas they use to determine financial aid packages. According to the plaintiffs, these schools favor wealthy applicants and are thus not need-blind as to all applicants, as required for the exemption (Henry, et al v. Brown University, et al, 1-22-cv-00125, No. 1, N.D. III., Jan. 9, 2022).

The named plaintiffs – Sia Henry, Michael Maerlander, Brandon Piyevsky, Kara Saffrin, and Brittany Tatiana Weaver – brought the class action under Section I of the Sherman Act against Brown, CalTech, University of Chicago, Columbia, Cornell, Dartmouth, Duke, Emory, Georgetown, MIT, Northwestern, Notre Dame, UPenn, Rice, Vanderbilt, and Yale. Defendants are all private universities regularly ranked among the top 25 universities in the country by U.S. News & World Report since 2003.

Plaintiffs allege that the universities participated in a price-fixing cartel designed to inflate the price of attendance for students receiving financial aid. Section 568 of the Improving America’s Schools Act of 1994 (the “568 Exemption”) applies to institutions of higher education that admit all students on a need-blind basis, which is supposed to operate without regard to a student’s or their family’s financial circumstances. The students argue that the schools do not qualify for the 568 Exemption because at least nine of them have for years favored wealthy applicants who are the children of past or potential future donors. The complaint notes that “[p]rivileging the wealthy and disadvantaging the financially needy are inextricably linked; they are two sides of the same coin”; by favoring the wealthy, the schools are also disfavoring the less wealthy. The complaint cites several examples of admissions officers at these schools admitting or courting students in exchange for expected donations from parents. Georgetown’s Dean of Admissions, for example, has candidly admitted that the larger a family’s donation, the more of a positive impact it may have on a student’s admission.

Columbia also concedes that its General Studies program admissions are not need-blind, even though its students tend to be less wealthy than those in Columbia’s other programs. At least some of the defendants, e.g., Notre Dame, Dartmouth, also allegedly engage in “enrollment management,” a largely secretive practice whereby students who do not need financial aid receive preference as a way to optimize the school’s overall admissions process.

Suit: Needs-Blind Admissions Applies to All Applicants, Even Those on Waitlist

Plaintiffs argue that the plain language and legislative history of Section 568 make it clear that in order to qualify for the exemption, a school must follow needs-blind admissions with respect to all applicants, including those on the waitlist. They quote former admissions employees from UPenn and Vanderbilt who have admitted giving preference to waitlisted students with greater ability to pay.

The complaint alleges that the other seven defendants – Brown, CalTech, Chicago, Cornell, Emory, Rice, and Yale – may or may not have adhered to need-blind admissions, but have nonetheless been members of the “568 Cartel” and conspired with the other defendants, whom they knew or should have known were not following need-blind admissions policies. The students argue that the 568 Exemption does not apply to them either.

Alleged overcharges amount to hundreds of millions.

The university defendants are members of the so-called “568 Presidents Club” whose members, starting around 2003, agreed on a common method for determining a family’s ability to pay, known as the Consensus Methodology. Plaintiffs argue that by collectively adopting this methodology and meeting regularly to implement it jointly, the universities have engaged in a conspiracy to artificially inflate the price of attendance. Over two decades, the schools have overcharged more than 170,000 financial-aid recipients by at least hundreds of millions of dollars, according to the complaint.

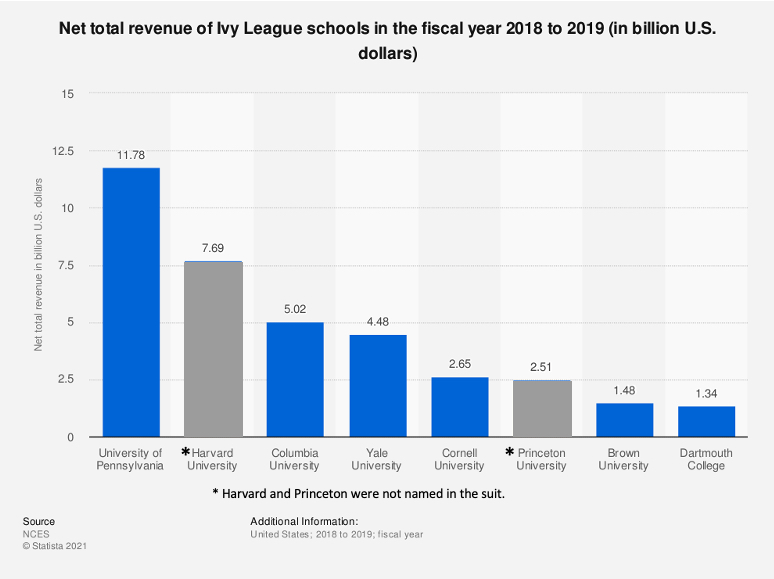

The students note that other universities, such as Harvard, declined to join the cartel because they wanted to offer more financial aid, and Yale announced it was withdrawing from the cartel in 2008 in order to be able to offer more aid to students, underscoring the relationship between membership in the cartel and higher net prices charged. Yale rejoined in 2018, the complaint notes.

These prestigious institutions are described as “gatekeepers to the American Dream” whose misconduct has limited upward mobility, especially for the low- and middle-income families who struggle to pay for a university education for their children. The complaint notes that wealthy students are disproportionately represented among the student bodies of all 16 institutions.

The alleged conspiracy consists of an agreement and concerted action to restrain price competition relating to the schools’ provision of financial aid for the students they compete for, thereby increasing the net price of attendance. Formed in 1998, the so-called 568 Cartel generally meets in person as a group at least twice a year. Additionally, members communicate regularly with each other on matters related to the alleged conspiracy through other means (e.g., phone calls, video calls, and emails). In addition to regular meetings, the 568 Cartel allegedly enforces its conspiracy by requiring each participant to submit a “Certificate of Compliance” and receive training in applying the Methodology, and imposing a common calendar for the collection of data from families.

The complaint argues that the schools deceitfully purported to be “need-blind” in their websites and promotional materials, which had the effect of “misleading a reasonably diligent person” and keeping them from investigating whether the 568 Cartel’s conduct gave rise to a cause of action.

Members of the class are defined as any U.S. citizen or permanent resident who, during the relevant time period (for most schools, 2003-present), has been a full-time undergraduate student at one of the named institutions, received need-based financial aid, and paid tuition, room, or board not covered by aid, as well as any family member or legal guardian who paid or committed to pay on behalf of these students. Plaintiffs seek an injunction to prevent future students from suffering injury, as well as compensation for current class members.

We’ve seen this before.

Nearly 30 years ago the DOJ Antitrust Division attempted a similar action but failed on the grounds that financial aid is charity and therefore not trade and commerce subject to the Sherman Act (United States v. Brown Univ. – 5 F.3d 658 [3d Cir. 1993]).

In 1958, MIT and eight Ivy League schools formed the “Ivy Overlap Group” to collectively determine the amount of financial assistance to award to commonly admitted students. The DOJ sued MIT and the schools, saying MIT violated Section 1 of the Sherman Act by agreeing with the Ivy League schools to distribute financial aid exclusively based on need and to collectively determine financial aid for students. The Ivy League schools signed a consent decree and MIT went to trial alone. The District Court said the agreement was plainly anti-competitive, so it applied an abbreviated version of the “rule of reason” to determine whether MIT’s pro-competitive defenses were plausible. The court held that the agreement constituted “trade or commerce” as defined by the Sherman Act, rejecting MIT’s argument that financial aid was an exempted charity. While it agreed that non-profits were covered by the Sherman Act, the Third Circuit reversed, directing the lower court to conduct a full-scale rule-of-reason analysis.

The Third Circuit wrote: “To the extent that higher education endeavors to foster vitality of the mind, to promote free exchange between bodies of thought and truths, and better communication among a broad spectrum of individuals, as well as prepares individuals for the intellectual demands of responsible citizenship, it is a common good that should be extended to as wide a range of individuals from as broad a range of socio-economic backgrounds as possible. It is with this in mind that the Overlap Agreement should be submitted to the rule of reason scrutiny under the Sherman Act.”

Circuit Judge Joseph F. Weis, Jr., dissented, saying the ruling upturned the antitrust law’s drafter’s aspirations of doing good. “Although Senator [John] Sherman [the writer of the Sherman Act] did not envision the application of the antitrust laws to schools in any circumstances, such a blanket exemption for educational institutions is not required to decide this case. It does seem ironic, however, that the Sherman Act, intended to prevent plundering by the ‘robber barons,’ is being advanced as a means to punish, not predations, but philanthropy. The result that the government seeks would divert funds that otherwise could be used for student aid to cover the expenses generated by treble damage suits. This is hardly the public good that Congress intended.”

Strong Defense Planned, Anticipated

Meanwhile, back to 2022, the 16 schools appear ready to defend their financial aid practices. Newsweek magazine contacted the schools for comment. A representative for Brown University told the magazine that while they hadn’t seen the suit, they believe it to be without merit. “Brown is prepared to mount a strong effort to make this clear. Brown is fully committed to making admission decisions for U.S. undergraduate applicants independent of ability to pay tuition, and we meet the full demonstrated financial need of those students who matriculate,” the Brown spokesman told Newsweek. Other schools echoed this response.

It will be interesting to see if the schools make the same “charity” argument that won them the day three decades ago. Note: Harvard and Princeton were not named in the suit.

Edited by Tom Hagy and Yamile Nesrala, J.D., for MoginRubin LLP.